Dermatitis is a general term that covers a range of conditions causing skin irritation. Contact dermatitis and eczema (atopic dermatitis) are common types of dermatitis

Symptoms of dermatitis

- Itchy, red skin

- Tiny bumps or blisters

- Crusted patches on the skin that if infected, develop a wet (weeping) look

- Thick, flaking, scaly, or dry skin (chronic eczema)

Contact dermatitis

As the name implies, contact dermatitis occurs after a person’s skin comes in contact with an offending substance. Contact dermatitis can be caused either by an allergic reaction or by simple irritation from things such as detergents or harsh soaps. All told, more than 3,700 contact allergens have been identified.

Poison ivy and poison oak are classic examples of allergens that can provoke allergic contact dermatitis. Brush against one of these plants and within a few days, you may develop itchy, red blisters. However, allergic contact dermatitis can also develop unexpectedly, even after you’ve been around a substance for some time with no problem. For instance, nail polish, nickel in jewelry, and certain medications—such as topical antibiotics and anesthetics—can suddenly cause a reaction.

Causes of allergic contact dermatitis include:

- botanical-based cosmetics that contain substances such as tree oil, lavender, and peppermint

- corticosteroids

- cosmetics

- fragrances

- hair dyes

- lanolin

- nickel

- poison ivy, poison oak, and other plants

- rubber

- shaving lotion*

- sunscreen*

- topical anesthetics

- topical antibiotics (Neomycin, Bacitracin)

*These can become a problem in the presence of sunlight.

Causes of irritant contact dermatitis include:

- acids and alkalis

- detergents

- environmental chemicals (such as insect spray)

- ethylene oxide

- oils and greases

- soaps

- solvents

Treating contact dermatitis

The first step in treatment is to wash the area thoroughly with mild soap to remove any trace of the substance causing the reaction. Avoiding the trigger is the next step. If you can’t determine the cause of the allergy or irritation, testing by an allergy specialist can help reveal the cause. Once you know the trigger and can avoid it, you might not need further treatment. Keep in mind that the route of exposure may not always be obvious; for example, the plant oils responsible for poison ivy may go first to the fur of your pet or the fabric of your gardening clothes and then transfer to the surface of your skin. Contact dermatitis usually clears up in about two to three weeks so long as you avoid further contact with the substance that caused it.

If further treatment is needed, wet dressings and soothing lotions can help ease itching and other symptoms. Other treatments for contact dermatitis include these:

- Corticosteroid creams or ointments. Available over the counter in varying strengths, these products ease itching and swelling. But in most cases, only potent, prescription-strength topical treatments will really help.

- Oral corticosteroids. For severe cases, your doctor may prescribe prednisone, which is usually tapered off gradually, over about 10 to 14 days, to prevent recurrence of the rash.

- Antihistamines. Over-the-counter non-sedating antihistamines such as fexofenadine (Allegra) and loratadine (Claritin) may help control itching.

Eczema

Eczema is a chronic inflammatory skin disease that affects 10% to 20% of children and 5% to 10% of adults. It often begins in infancy as an intensely itchy rash. Most people can’t help scratching, which leads to further irritation and the possibility of skin infection caused by injury to the skin. The injured skin develops chronic inflammation and its function as a barrier is impaired.

Close to 50% of people with eczema have a family history of allergic diseases.

Treating eczema

Treatment involves rehydrating the skin by soaking in warm (not hot) baths or showers and then promptly applying moisturizers with a low water content to lock in the moisture. Thick creams, such as Nutraderm, Aquaphor, or Eucerin, do a good job. Choose creams without fragrances and preservatives. However, you should limit use of soaps and shampoos to once or twice a week, since soap products exacerbate skin dryness by removing natural skin oils.

Management also includes soothing the ferocious itch with regular use of an antihistamine. A long-acting, non-sedating oral antihistamines such as over-the-counter cetirizine (Zyrtec) can be used during the day and a sedating antihistamines like diphenhydramine (Benadryl) can be used at bedtime, since it can help with sleep also.

If eczema is not controlled by moisturizers and antihistamines alone, then doctors will recommend a prescription or over-the-counter topical corticosteroid to reduce inflammation in the skin. The corticosteroid should be applied to the skin first and the moisturizer applied over the top.

Corticosteroid creams and ointments are effective, but a major drawback is that potent steroids cannot be used for more than a week or two on the face—where symptoms often appear—because they gradually thin the skin and cause small blood vessels to break. Long-term use can also cause loss of skin pigmentation. Avoid extended use in areas of the skin that are warm and moist, such as in skin folds, because of increased absorption. Several trials show that once eczema is controlled, people can take a proactive approach to prevent flare-ups by applying a topical corticosteroid twice a week to areas that have healed but are prone to eczema.

Severe cases of eczema are sometimes treated with medications that suppress the immune system, such as tacrolimus (Protopic) and pimecrolimus (Elidel). These medications have proved effective in lessening the need for corticosteroids, and they can be used on the face.

Prevention of eczema

To prevent or reduce eczema flare-ups:

- Avoid exposure to extreme temperatures, dry air, harsh soaps, perfumed products, and bubble baths.

- Use blankets and clothing made of cotton. Avoid more irritating fabrics, such as wool. Avoid stiff synthetics, such as polyester.

- After showering or bathing, pat dry (rather than rub). That way, you leave a little moisture on your skin. Then apply a moisturizing cream or lotion to trap moisture in the skin.

- Use a humidifier.

The Skin

Though most people seldom stop to appreciate their skin, skin is the body’s largest organ, and it’s much more than a simple covering. Your skin weighs about nine pounds, and it carries out a number of functions that help maintain health.

Your skin is actually a complex fabric of tissues working together to protect you in multiple ways. On the most obvious level, it forms a defensive barrier, protecting your inner organs from foreign invaders such as bacteria and viruses. More than just a passive barrier, skin actively wards off infection by way of its Langerhans cells, which form the front-line defenses of the immune system in the outermost layer of skin.

Your skin is also a sensory organ. Nerve endings on its surface pick up and relay information about the surrounding environment to your brain. Your brain then translates these nerve impulses into the sensations of heat and cold, as well as touch, pressure, and pain. If you touch a scalding pot, for example, the warning signals cause you to pull back in an instant, before further harm is done. Or, if the room is simply too hot or too cold, these sensations tell you to turn on the fan or put on a sweater. But your skin actively contributes to temperature control, too. When you’re hot, it helps cool you down by sweating and dilating its blood vessels. When you’re cold, those blood vessels constrict to conserve heat deep inside your body.

Finally, the skin is also a manufacturing plant, using the sun’s energy to make vitamin D, which is essential to many body functions.

Skin layers, explained

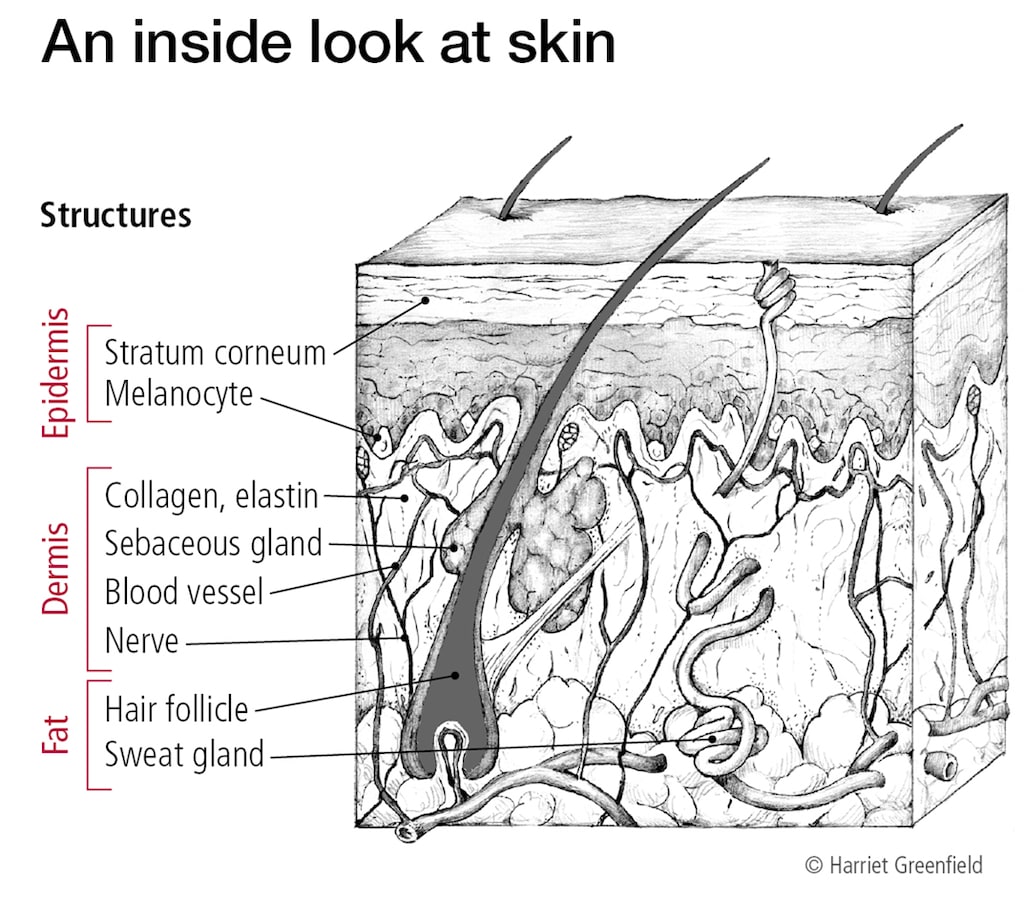

To carry out all these functions, the skin relies on the specialized structures in its three layers—the epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous layer, sometimes called the hypodermis.

The outermost layer

The epidermis—the outermost layer of the skin—is a protective, physical barrier, about as thick as a piece of paper. The very top portion of the epidermis is known as the stratum corneum. It’s composed of cells called keratinocytes that produce a tough protein called keratin, forming a flexible outer shield. The keratinocytes die as younger living cells from the lower part of the epidermis rise to the surface from below. Finally, the older cells are rubbed off or fall off. This continuous cycle completely renews the skin surface about once a month.

The epidermis plays a key role in protecting you from the sun’s radiation. In particular, pigmented cells called melanocytes are located at the bottom of the epidermis. These cells produce the melanin, or pigment, that colors skin and helps protect against ultraviolet radiation. When exposed to sunlight, the melanocytes churn out more melanin, and the skin darkens to help shield against further damage. If the melanocytes become cancerous, the condition is termed melanoma.

The middle layer

The dermis lies directly beneath the epidermis. It is a thicker layer that contains collagen, blood and lymph vessels, nerves, hair follicles, and glands that produce sweat and oil. Blood vessels in the dermis expand or contract to maintain a constant body temperature. White blood cells patrol the dermis to fight infectious microbes that manage to break through the epidermis. Cells called fibroblasts secrete collagen, which gives the skin its strength and firmness. Elastin fibers made of protein in the dermis give skin its elasticity.

The deepest layer

The subcutaneous tissue, which consists of connective tissue and fat, lies between the dermis and underlying muscles or bones. It, too, contains blood vessels and infection-fighting white blood cells, but not to the same extent as in the dermis. Fat in the subcutaneous layer stores nutrients and insulates and cushions muscles and bones.

Nails and hair

Your nails are skin, too. They’re a thickened, hardened form of epidermis. Nail cells originate from the base of the nail bed. They die quickly, but unlike the keratinocytes, they aren’t sloughed off. They’re also composed of a much stronger form of keratin. Thus, a nail is simply a sheet of keratin like the topmost layer of skin, but much harder and thicker. Hair, however, is a thin fiber made of many overlapping layers of keratin, which is produced in the hair root.