Despite the name, heart failure does not mean the heart has failed completely. Instead, it means the heart isn’t pumping efficiently enough to meet the body’s need for blood.

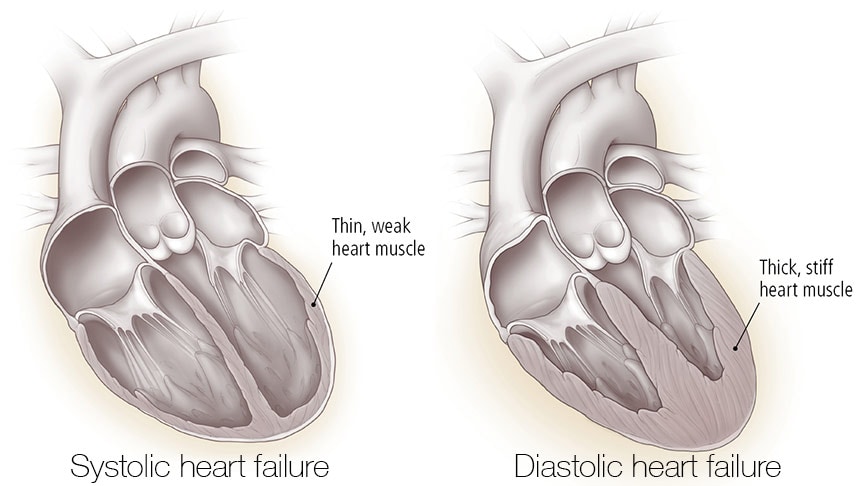

There are two main types of heart failure: systolic heart failure and diastolic heart failure. But doctors are increasingly referring to them by more precise terms based on the heart’s pumping function, known medically as the ejection fraction.

Diastolic heart failure (preserved ejection fraction): In diastolic heart failure, the heart muscle stiffens and often thickens, which prevents the ventricles from relaxing enough to fill up with blood. As with systolic heart failure, the result is a shortfall in the amount of blood delivered to the body.

It’s called the ejection fraction because it gauges the percentage of blood in the left ventricle that’s pumped out (ejected) each time the ventricle contracts. Contrary to what many people believe, a normal ejection fraction is not 100%. Even a healthy heart pumps out only about half to two-thirds of the blood in the chamber in one heartbeat. So, a normal ejection fraction lies somewhere in the range of 55 to 65%.

In systolic heart failure, the ejection fraction is low, so it’s known as heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. In diastolic heart failure, the ejection fraction stays at a normal or near-normal level, so it’s known as heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. However, the heart muscle is stiff and cannot relax, and the ventricle cannot fill properly.

In both types of heart failure, stress hormones rise to compensate for the weakened heart muscle, pushing the heart to beat faster and harder. Blood vessels narrow in an effort to keep blood pressure stable to make up for the heart’s lack of power. To keep blood flowing to the heart and brain, the body diverts blood away from less important tissues. In turn, the diminished blood flow to the kidneys activates a set of hormones that prompt the body to retain sodium and fluid in an attempt to supplement the total volume of circulating blood.

In the short run, these fixes enable the heart to deliver a near-normal level of blood to the tissues. But the solution is only temporary. Over time, these compensatory measures can’t keep up, and the heart weakens further.

Causes of heart failure

The defining characteristic of heart failure is a malfunctioning heart muscle. But many different circumstances can lead to this endpoint.

Coronary artery disease. About two of every three cases of heart failure can be traced back to coronary artery disease—especially if a heart attack damages the heart muscle. This damage prevents the heart from beating forcefully enough to push blood throughout the body. Approximately a quarter of people who survive a heart attack develop heart failure within the next year.

High blood pressure. High blood pressure forces your heart to work harder, causing the heart muscle to thicken. The thickened muscle uses more oxygen and is unable to fully relax between contractions. As a result, the heart can’t beat as forcefully as needed. High blood pressure precedes heart failure in 75% of cases.

Heart valve disorders. Faulty heart valves that don’t open or close efficiently put additional strain on the heart. Narrowed valves don’t allow blood to pass between the heart’s chambers, and leaky valves let blood travel backward between beats. This forces the heart to do double duty to keep blood moving.

Congenital heart disorders. These defects, which occur before a child is born, can affect the heart’s chambers, valves, or blood vessels. Most are detected and repaired during infancy or childhood, but undetected or lingering damage may affect the heart’s ability to function normally.

Diseases of the heart muscle. Known as cardiomyopathies, these diseases damage heart muscle in different ways, causing the ventricle walls to either stretch and thin, become stiff and rigid, or grow abnormally thick.

Heart rhythm disorders. An abnormally fast heartbeat can produce structural changes in the heart’s left ventricle. The most common of these rhythm disorders (arrhythmias) is atrial fibrillation, which increases the risk of heart failure.

Diabetes. Over time, uncontrolled diabetes weakens the heart muscle by causing coronary artery disease and damage to the kidneys. Diabetes also seems to directly impair the heart’s pumping capabilities.

Symptoms

Heart failure causes two major problems for the body: (1) the tissues and organs don’t get enough oxygen, and (2) fluid builds up in the lungs and tissues. Each of these spawns a series of distinct complaints. Lack of oxygen, for example, can lead to fatigue and mental confusion, while fluid buildup can cause weight gain and swelling in the feet and ankles. If you’re unfamiliar with heart failure, you could easily interpret these as isolated symptoms. People often mistakenly attribute the early signs of heart failure to being out of shape, being overweight, or just getting old. Adding to the confusion is the fact that the symptoms can wax and wane over the course of the illness.

At first, heart failure generally affects only one side of the heart. The side of the heart where the weakness begins influences which symptoms predominate.

- When heart failure affects mainly the left side of the heart, the left ventricle can’t propel an adequate volume of blood throughout the body. As a result, blood backs up into the lungs, and the symptoms are likely to involve wheezing, coughing, and shortness of breath.

- When mainly the right side is affected, the right ventricle has trouble pumping blood to the lungs. As a result, blood backs up into the veins and builds up in body tissues, and the main symptoms may be swelling in the legs and abdomen.

As the condition advances, both sides of the heart may eventually be affected. Paying attention to your symptoms can tell you a lot about what is happening inside your body.

Is your heart failure getting worse?

Heart failure can worsen rapidly, so people with this serious condition need to keep close tabs on their symptoms. You should call your doctor at the first signs of fluid retention. The following is a quick guide to interpreting your symptoms:

- Sudden weight gain. Your body is holding on to extra fluid.

- Unexpected but gradual weight loss. If you lose 5% to 10% or more of your weight over six months to a year without dieting, it could be from the loss of appetite that often comes with advanced heart failure.

- Loss of appetite. Swelling in your intestines and liver can cause pain. (This swelling can also cause trouble absorbing food or drugs from the digestive tract.)

- Fatigue. Your heart isn’t delivering enough oxygen-rich blood to your tissues.

- Cough and wheezing, or shortness of breath. Fluid is collecting in your lungs.

- Swelling. Your body is holding on to excess sodium and fluid; poor pumping is causing blood to get stranded in your lower body (feet, legs, abdomen).

- Mental confusion. Your heart isn’t pumping enough oxygen to your brain.

- Increased heart rate. Stress hormones released when pumping gets weaker cause your heartbeat to speed up, giving the feeling that your heart is racing or throbbing or that your heart rhythm has noticeably changed.

- Sleep problems. Fluid collecting in the lungs makes breathing difficult when you’re lying down.

Diagnosis

Your doctor may ask for details about your symptoms, such as how many blocks you can walk without becoming short of breath and whether you suddenly wake up at night because of severe shortness of breath.

During your physical examination, your doctor will listen to your lungs for abnormal breathing sounds that indicate fluid buildup. Other physical tests include pressing on the skin of your legs and ankles to check for swelling and feeling your abdomen to check the size of your liver. Fluid backup from the heart can cause liver swelling.

Other tests you may have include the following:

- ECG. This test may show if the walls of your heart are thicker than normal and can also reveal an arrhythmia or signs of a previous heart attack.

- Chest x-ray. An x-ray image of your chest can show if your heart is enlarged and if you have fluid in your lungs.

- Echocardiogram. This test can show changes in the heart’s wall, chambers, and valves. It can be used to determine the ejection fraction (the volume of blood pumped out of the left ventricle with each contraction).

- Radionuclide ventriculography. This test, also known as a multiple-gated acquisition (MUGA) scan, involves an injection of a radioactive liquid that shows up in images made with a special camera that takes pictures of your beating heart. It measures your ejection fraction.

Treatment

Treating heart failure focuses on easing your symptoms, keeping you out of the hospital, and helping you live longer. These treatments include self-care strategies, medications, and for some people with advanced disease, ventricular assist devices, implanted defibrillators, or a heart transplant.

Self-care strategies

Keeping close track of your symptoms can go a long way toward managing them more effectively. Use a small notebook, a chart, a computer, or a smartphone to record your symptoms. At the end of each day, fill in your symptoms and note their severity on a scale of 1 to 5.

Monitor your weight

Weight gain is the earliest sign that your heart failure is getting worse. Unchecked, fluid buildup can quickly escalate into a life-threatening situation. Most people will retain 8 to 15 pounds of excess fluid before they begin to notice swelling and other outward signs. Since a weight gain of 2 pounds in a day is a call to action, you could be well on your way to a serious problem by the time these symptoms appear.

The good news is that you can tell if you’re beginning to retain fluid merely by getting on the scale every morning. Taking corrective steps at this early stage—for example, paying more attention to salt and fluid intake or adjusting your dose of diuretic—can reverse the trend before it becomes a crisis.

To get the most accurate assessment, you first need to determine your dry weight—that is, your weight without excess fluid accumulation. This number is unrelated to obesity, body mass index, or percentage of body fat. It is important only for the purposes of helping you to monitor fluid buildup due to heart failure. If you’ve recently been in the hospital and treated for fluid buildup, your weight when you were discharged is likely to be your dry weight. Otherwise, ask your doctor or nurse what your starting-point weight should be.

Once you have your dry weight as a reference point, follow these steps to get the best results:

Weigh yourself every day at the same time. A good time to do this is in the morning after you urinate but before you eat breakfast.

- Use the same digital scale every day.

- Weigh yourself without clothing or in underwear only.

- Log your results immediately after weighing yourself, so you don’t forget.

- Keep your weight logs and bring them with you to your doctor visits.

Your goal is to keep your weight as close as possible to your dry weight, so when you look for trends, compare your daily weight to your dry weight, not to the previous day’s results.

A smart scale will record your weight and send the data automatically to your computer, tablet, or smartphone. This enables you to easily spot the trends. If your doctor is based at a heart failure clinic that’s set up to receive data electronically, you can send the information there, too. Then, if the nurse managing your case spots an alarming gain, you might receive a call telling you to follow certain steps to get rid of the extra fluid.

You need to take action if:

- you gain 2 or more pounds in one day

- you gain 4 pounds in a week

- you notice signs of swelling

If any of these applies, you should call your doctor or nurse for advice.

Balance salt and fluids

A healthy, low-sodium diet is a crucial part of self-care for people with heart failure. Sodium, one of the two chemical components of salt, inhibits the elimination of water from your body. For tips on trimming sodium from your diet.

Limiting your liquid intake will help control fluid overload. For most people with heart failure, that means no more than 8 cups of fluid per day. But you might be surprised at what counts as a fluid.

Note that caffeinated drinks are equivalent to noncaffeinated beverages when it comes to calculating daily fluid intake. As for alcohol, ask your physician what amounts, if any, are safe for you.

If you feel thirsty or have a dry mouth, these tips may help:

- Rinse your mouth with water but spit the water out. Do not swallow.

- Chill mouthwash and gargle for a fresh feeling.

- Add a few drops of lemon juice to ice cubes or crushed ice and slowly let the ice melt in your mouth.

- Keep hard candies, mints, and gum available. Some people find the sugar-free varieties to be more thirst-quenching.

- Suck on lemon or lime slices.

- Eat frozen grapes or other frozen fruit.

Monitor your potassium

Your body depends on potassium to help control the electrical balance of your heart. This key mineral also helps you metabolize carbohydrates and build muscle. Low potassium levels can cause muscle weakness and heart rhythm disturbances. On the other hand, too much potassium can cause dangerous heartbeat irregularities and even sudden death.

Based on the drugs you’re taking, your doctor can decide if you’re at risk for abnormal potassium levels—either high or low. In addition, you should have your blood tested often to measure your level of potassium. Many heart failure experts recommend that blood potassium concentrations be targeted at around 4.0 millimoles per liter. However, your doctor will determine a safe level for you based on the medications you are taking and adjust your treatment plan as needed.

If it’s low, the solution may be as simple as taking potassium supplements. If it’s high, you may need to cut back on certain foods.

If your doctor tells you to reduce your potassium intake, these tips can help:

- Soak or boil vegetables and fruits to leach out some of the potassium.

- Avoid foods that list potassium or K, KCl, or K+—chemical symbols for potassium or related compounds—as ingredients on the label.

- Stay away from salt substitutes. Many are high in potassium.

- Avoid canned, salted, pickled, corned, spiced, or smoked meat and fish.

- Avoid imitation meat products containing soy or vegetable protein.

- Limit high-potassium fruits such as bananas, citrus fruits, and avocados.

- Avoid baked potatoes and baked acorn and butternut squash.

- Don’t eat vegetables or meats prepared with sweet or salted sauces.

- Avoid all types of peas and beans, which have a naturally high potassium content.

Medications

Medications for heart failure include the following types of blood pressure drugs, which have additional benefits for people with heart failure.

Diuretics. These drugs remove excess body fluid by increasing urine output. Low doses of a potassium-sparing diuretic can help people with heart failure live longer.

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs). These make it easier for the heart to pump blood throughout the body.

Angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitor (ARNi). This new class of drug combines an ARB called valsartan with a drug called sacubitril that works by increasing levels of peptides that protect the heart. The new combination medication, called Entresto, appears to lower the risk of death for people with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction by about 20%.

Beta blockers. These slow the heart, easing its workload.

Additional medications to ease heart failure may include the following:

Digoxin. This drug, which strengthens the heart’s ability to contract, is sometimes prescribed in low doses in people with advanced heart failure.

Anticoagulants. These medications help prevent blood clots and are sometimes prescribed for people who need long periods of bed rest.

Your doctor also will address the underlying cause of your heart failure. Heart failure related to coronary artery disease may require additional medications.

Devices and surgeries

You may need procedures or surgeries to treat underlying causes of heart failure, including angioplasty, bypass surgery, or surgery to replace or repair a faulty heart valve. Some people may benefit from a special monitoring device that can help them avoid doctor visits—and perhaps keep them out of the hospital.

As heart failure advances, medications may no longer do enough. At that point, options include the following devices and procedures.

Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD). Some people with severe heart failure may receive this implanted device, which identifies and responds to irregular heart rhythms. An ICD does not ease symptoms of heart failure, but it can help protect against sudden cardiac arrest.

Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT). Also known as biventricular pacing, this procedure uses a pacemaker to make both the right and left ventricles contract at the same time. Because this therapy improves the heart’s efficiency and increases blood flow, it may help relieve heart failure symptoms in some people.

Heart transplant. Once considered risky and experimental, heart transplantation is now considered the “gold standard” treatment for people with end-stage heart failure, which means a person has severe symptoms (even when resting) that don’t respond to drug treatment. Advances in antirejection medications, surgical techniques, and selection of donors have increased survival rates for this major operation. From the early 1980s, the one-year survival rate following a heart transplant rose from below 70% to around 88%. Recent data suggest that living for 15 to 20 years after a heart transplant is becoming more common. In the United States, about 3,000 people are on the waiting list for a heart transplant. Each year, about 2,000 hearts become available for donation.

Ventricular assist device (VAD). A ventricular assist device (VAD) is a battery-driven pump implanted in the chest. Most support the left ventricle and are known as LVADs; they receive blood from the left ventricle and deliver it to the aorta. Right ventricular assist devices (RVADs) receive blood from the right ventricle and deliver it to the pulmonary artery. The machine consists of a pump, a control system, and an energy supply. The pump can be located inside or outside the body, while the control system and energy supply consoles are outside the body.

VADs were initially used to help people recover after a heart attack or other cardiac injury. But after heart transplantation became more established, doctors began using the devices to keep people alive until a donor heart became available. And as they become more durable, smaller, quieter, and more self-contained, VADs are now being increasingly used as a permanent alternative to a heart transplant.

Heart failure affects an estimated 5.8 million adults in the United States. People over age 40 have about a one-in-five chance of developing the condition in their lifetime. Life expectancy after diagnosis averages five years, but earlier diagnosis and rapid advances in treatment are making it possible to slow the onset of debilitating symptoms, and many people with heart failure go on to enjoy many more years of fulfilling life than that.